Cats on leashes, full-size outdoor kitchens, potted herbs, endless summers… those mainland Europeans know how to do camping.

But so does Madame Ulysse. She’s gently obsessed by tents. How did that happen? She tells us all…

Fourteen tents and one house

I have 11 tents in my house right now, and at least three others out and about in other homes.

And that isn’t counting the ones that, over the years, have come and gone forever. Where did my love of tents come from and what has it meant?

More recently and perhaps not unrelated in my psyche or genetic inheritance, I have noted also a developing attachment to Turkish carpets. I’ve run out of rooms to put them in – but happily, they go very well inside a tent. What does this all mean?

From stone to canvas

We didn’t go camping when we were children (except perhaps for an hour or two in a makeshift tent in the back garden).

But we did holiday in remote Welsh cottages, smelling of wood smoke and with no electricity or running water, so I was used to roughing it.

The light, warm airiness of a tent was a revelation after the solid dampness of stone walls, and certainly trumped the caravan and mobile home for glamour, and the potential choice of location.

There was a rather unpleasant camping experience near Windermere in the Lake District, which I was prepared to gloss over (in spite of the rain, the inadequate groundsheet, the broken-zipped sleeping bag and a general sense of dread) because it may have been coloured by my morning sickness.

Did it all start with an affordable holiday?

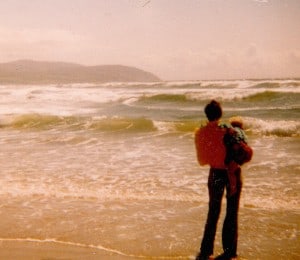

I came to camping slowly, through the exigencies of young impoverished parenthood – the tiny ridge tent for two adults and a nine-month old baby, the single Camping Gaz ring in the footwell of the Ford Anglia, the sodden British summer weather.

We roamed the west coast of Scotland from Kintyre to Cape Wrath, fishing for brown trout in tiny streams and sea trout on the shore. We learned to avoid the midges by sitting in the car from 4pm to 6pm (not necessarily going anywhere).

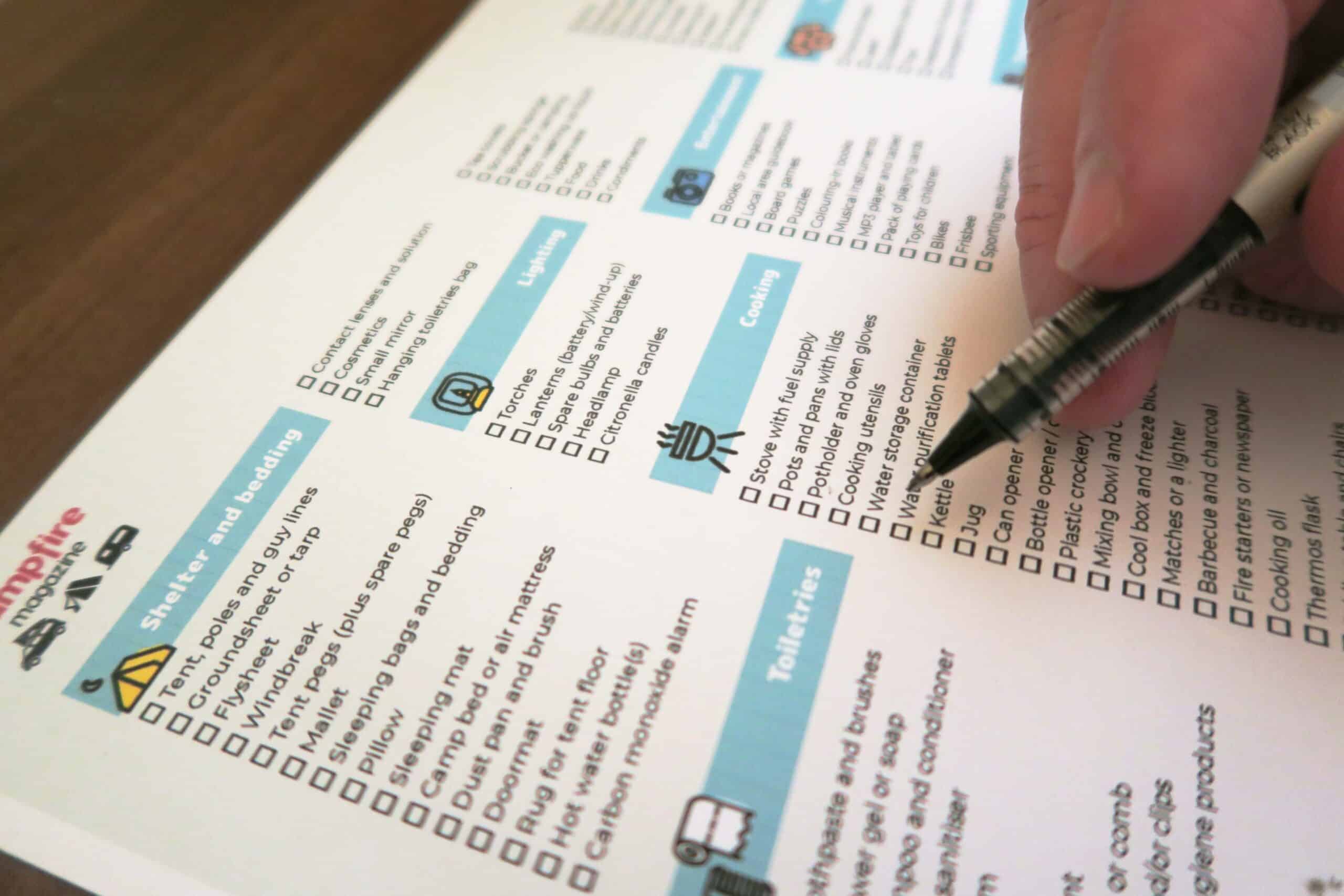

We became adept at pitching the tent in the worst possible conditions – we didn’t want to learn that but were forced to by a hearty fellow camper (from the Min of Ag and Fish, it turned out) on a headland swept with horizontal rain. He appeared out of the gloom at our car window as we were hunkering down for the night and insisted on helping us put up the tent. Over time, we acquired kit, and caboodle. The Blue Box full of small essential camping items accompanies me to this day.

France, pine trees and crashing waves

It was only when we went to France with our tent – now a larger ridge tent, heavy green cotton, Polish-made by Relum – that I ceased to see camping as a stopgap on the way to something better and fully embraced the beauty, ingenuity and satisfaction of life under canvas.

In the early years, when we still had no money, I would be piqued by my envy of other European campers. They had tents we had never seen in the UK – domed, multi-roomed, made of magically light and indestructible earth-coloured fabrics.

People had outdoor kitchens, fridges, some even had washing machines. And the time they had to live like that! We were on holiday for two weeks – they stayed for months, it seemed. Time enough for window boxes, birds in cages and cats on leashes. And all in the sunshine, perfumed by pine trees, accompanied by the constant roar of the Atlantic ocean.

There followed golden years returning to the same primitive French campsite in the pines, as near as you could get to the ocean without wild camping in the dunes. We now had two large Relum blue canvas tents and gathered our family and friends around us, sometimes for weeks at a time (we had chosen careers in local government and academia – in the days when you had a choice, and paid holiday time was a legitimate part of working life).

We lived under the trees on a carpet of pine needles. There were cold-water showers in little wooden shacks and hole-in-the-ground toilets. Above us, red squirrels chattered their way across the forest or stopped to nibble and drop their pine-cone litter on us.

Changing seasons

In July and August, the place was packed; in June and September practically empty – very different experiences.

Out of season, the site was green and rainy, with small mammals and birds close to the tent, nightingales at night and only Northern Europeans and surfers on the beach. In high season, all the interest was in our very close human neighbours – solid French families from Toulouse, French families who couldn’t afford to go to the Mediterranean, professionals from the Pyrenees, young people with hippy tendencies from all over the world, Welsh surfers in campervans, but very few English people. Our French improved a lot.

At night you could sit on the dunes and watch the lightning play backwards and forwards over the ocean, or make your way to the village to one of the noisily competing events beginning at 11pm and ending in the early hours.

By day, everyone was on the beach, including icecream sellers who would trudge across the vast sands in the afternoon heat with enormous cool boxes, and, more bizarrely, traders of hot apricot jam-filled doughnuts, calling “Beignets! Qui veut de beignets?” Small planes would fly along the shore trailing advertisements for the new big supermarket six miles away or for the next event at the bull-ring in the village.

Camping next to the sea

The ocean mesmerised and terrified us. It lured us in and we would share the breaking waves with hundreds of shining mullet who flipped away from the shore just as the wave crashed down.

There was only one small area of surveyed bathing much further down the coast near the village, so every now and then the maîtres nageurs-sauveteurs would drive along the beach and whistle all of us reckless swimmers out of the water.

Reckless, because to swim meant we had to get past the waves and then we were into the strong currents that could pull you out into the open ocean. To get out of the sea took some nerve too. The surf would beat you into the sand, drag you back under the next wave, tear off your clothes and earrings and watch. Finally the ocean would throw you, breathless with panic, onto the enormous shore to dry out until you took your place, salted and brown, with the rest of the driftwood.

..to be continued….meanwhile, have a look at our feature on our favourite tents.

Quick Pitch Tents and Instant Tent Guide 2021 – Which tents are the fastest?

Ferries to France – what about Hull?

Ferries to France – what about Hull?

If you live in Scotland or the north of England, then getting to France is easy. We used to drive all the way to Portsmouth, but then spent a while working out the comparative costs and time of a ferry from the south versus a ferry from Hull.

Surprisingly, we found that, even if you’re heading to the south-west of France, it’s cheaper and less distance to go from Hull to Zeebrugge.

It’s overnight – leaving Hull at 18.30 and arriving in Belgium at breakfast time. Not only does it get you in the holiday mood faster, you get to do the interesting driving at the continental side rather stop-starting all the way down the M1 or M6. And, you could do worse than spend a day or two in Hull – City of Culture in 2017.

Sadly, food on the ferries isn’t what it used to be. I can remember looking forward to the semi-luxury of a buffet or restaurant meal. These days, it’s expensive and mediocre and every part of the ship shouts sales messages at you – from drink-more leaflets on every table to buy wifi, cuddly toys, perfume, gin and more.

Take your own food?

We used to take our own food ready to warm up in the microwaves provided for baby food. No more. Microwaves have gone for some unfathomable safety reason.

Now, you’ll either have to (literally) stomach the cost of poor on-board food, or go prepared. We take a selection of salads and dips or (if we’re being very organised), make up insulated food flasks filled with stew, soup or curry.

Ferries to France – what about Hull?

Ferries to France – what about Hull?